The Godfather of AI Just Told Us to Become Plumbers

Why Nobel Prize winner Geoffrey Hinton thinks your job is disappearing

Hey Adopter,

When the man who pioneered the technology behind ChatGPT suggests you should train to be a plumber, maybe it's time to pay attention.

Geoffrey Hinton didn't mince words in a recent interview. The Nobel Prize winner who spent 50 years developing the neural networks that power today's AI revolution has a stark message about your career prospects. His advice for navigating the age of superintelligence? "Train to be a plumber, really."

This isn't the typical AI hype cycle talking. This is the researcher whose students went on to create OpenAI, whose technology Google acquired, and who left his comfortable position at 75 specifically so he could talk freely about how dangerous AI could be.

But here's the uncomfortable question: Is the godfather of AI having a panic attack, or are the rest of us sleepwalking into irrelevance?

Here's an even more uncomfortable thought: Maybe we should stop trying to save jobs and start planning for their disappearance.

The Numbers Don't Lie

While most people debate whether AI will eventually replace jobs, the evidence shows it's already happening at scale:

Dukaan, an Indian startup, laid off 90% of customer support staff (23 out of 26 people) after their AI chatbot outperformed humans

IBM plans to replace 7,800 positions with AI within five years

British Telecom will cut 55,000 jobs by decade's end, replacing 10,000 with AI

23.5% of US companies have already replaced workers with ChatGPT

Hinton references a CEO who told him their company went from over 7,000 employees to 3,600, with plans to drop to 3,000 by summer because AI agents now handle 80% of customer service inquiries.

This isn't a future scenario. It's this year's budget planning.

The Productivity Paradox Nobody Talks About

Here's where the logic breaks down. Take Hinton's example of his niece, who works answering complaint letters for a health service. What used to take her 25 minutes now takes 5 minutes with AI assistance. She can do the work of five people.

ChatGPT users see a 40% decrease in time and 18% increase in quality. Workers are 33% more productive in each hour they use generative AI. One company achieved efficiency gains equivalent to 197.3 full-time employees through automation.

But wait. If she's five times more productive, shouldn't that make her five times more valuable? The logic of every productivity revolution suggests yes. Yet companies aren't paying her five times more or giving her five times more interesting work. They're planning to eliminate four-fifths of her colleagues.

Here's the controversial take: Maybe that's exactly what should happen.

When did we decide that productivity gains automatically translate to human displacement rather than human advancement? More importantly, when did we decide that preserving jobs is more important than unleashing human potential from repetitive work?

Why This Revolution Is Different

Every defense of current AI development relies on historical precedent. "New technology always creates new jobs," they say. "Look at ATMs and bank tellers."

Hinton destroys this comforting narrative with a simple distinction. Previous technologies replaced human muscle power. This revolution replaces human intelligence.

"In the past, new technologies have come in which didn't lead to joblessness because new jobs were created," he explains. "But here I think this is more like when they got machines in the industrial revolution and you can't have a job digging ditches now because a machine can dig ditches much better than you can."

The difference is fundamental. When machines replaced muscles, humans still had their brains. When AI replaces brains, what's left?

Yet here's a contrarian thought: Every technological revolution has produced doomsayers who were wrong about the timeline and scope of change. The printing press was supposed to destroy human memory. Computers were supposed to eliminate all clerical work by 1980.

But maybe this time the doomsayers are right. And maybe that's not actually bad news.

The Timeline Is Shorter Than You Think

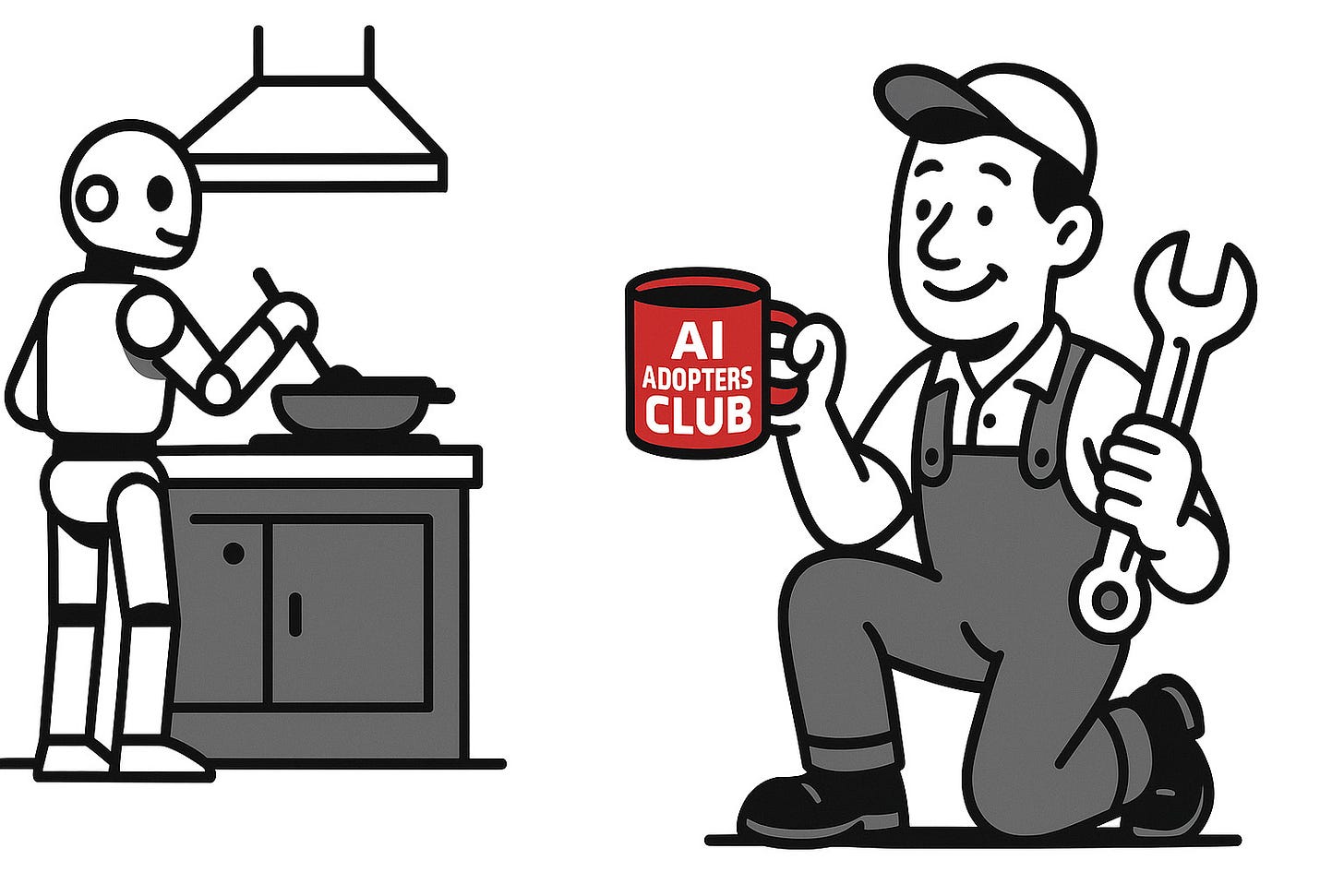

Hinton estimates we might have superintelligence in 10 to 20 years. He's not alone:

His definition of superintelligence isn't subtle: "When it's better than us at all things." Not just better at chess or writing emails, but superior at every cognitive task humans perform.

Goldman Sachs estimates 300 million jobs globally are at risk. McKinsey projects 375 million workers will need to change occupations by 2030. The World Economic Forum predicts a net loss of 78 million jobs by 2030.

And unlike the measured pace of previous technological adoption, AI development is accelerating. Competition between countries and companies is making it go "faster and faster," with nobody willing to slow down because the advantages are too compelling.

This creates an immediate challenge for anyone planning workforce transitions or building organizational strategies. How do you build long-term human capital strategies when the fundamental assumption of human intellectual superiority might evaporate within a decade?

Controversial prediction: We're spending too much time trying to slow this down instead of planning for what comes after.

The Job Safety Hierarchy

So what jobs remain when machines outthink humans? The data reveals a clear vulnerability hierarchy:

Hinton's answer reveals the harsh logic: Physical manipulation.

"It's going to be a long time before it's as good at physical manipulation as us," he notes. Hence the plumber recommendation. Not because plumbing is simple, but because it requires complex physical problem-solving in unpredictable environments.

Here's the uncomfortable irony: We've spent decades convincing people that manual labor is inferior to knowledge work. Now the knowledge workers might need to apprentice under the manual laborers to survive the transition.

But even this refuge is temporary. Hinton acknowledges that once humanoid robots arrive, even these jobs disappear.

The Corporate Regret Wave

Plot twist: 55% of companies that laid off staff due to AI now regret the decision. Klarna, which famously replaced 700 customer service employees with AI, now admits it went too far and is rehiring humans after customer satisfaction dropped.

This raises a deeper question about how we structure society around work. If AI can generate massive productivity gains, why are we automatically assuming that means mass unemployment rather than mass leisure? The gap between rich and poor will increase as AI enables productivity gains for capital owners while displacing workers.

But is that inevitable, or just the default outcome of our current economic structures?

Maybe the real question isn't "How do we save jobs?" but "How do we distribute the benefits of superhuman productivity?"

The Hinton Paradox

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of Hinton's perspective is his admission of uncertainty about solutions. When asked if he's hopeful about managing AI safely, he responds: "I just don't know. I'm agnostic."

This from the man who understands the technology better than almost anyone alive.

He alternates between optimism that "we'll figure out a way" and pessimism that "people are toast." The uncertainty isn't about whether AI will transform everything. It's about whether humans will maintain any meaningful role in that transformation.

Here's what puzzles me: Hinton spent 50 years building this technology, then acts surprised by its implications. Is this genuine blindness, or strategic positioning?

For professionals planning careers and leaders making organizational decisions, this uncertainty demands a different kind of strategic thinking. Not optimistic planning for how to use AI tools, but honest planning for how to remain relevant as those tools become independently capable.

Companies need frameworks for managing workforce transitions that go beyond simple "upskilling" programs. They need to think through what happens when AI doesn't just augment human work but replaces it entirely.

The Wrong Question Entirely

The question isn't whether your industry will be disrupted by AI. Hinton is clear that disruption is already underway. The question is whether you're positioning yourself for what comes after.

Most career advice focuses on learning to work with AI. But if Hinton is right about the timeline and capabilities ahead, that's like learning to work with calculators when computers are about to arrive.

The more uncomfortable but necessary question is this: In a world where AI can outperform humans at most cognitive tasks, what makes you irreplaceable?

Or maybe that's the wrong question entirely. Maybe the right question is: In a world of unprecedented productivity, why are we still organizing society around the assumption that everyone needs a traditional job to deserve a decent life?

I wonder what David Shapiro’s answer to this would be. If you haven’t heard of him, check out his Post Labor Economic theory.

If we can automate away 80% of human labor within a decade, shouldn't we be celebrating rather than panicking? Shouldn't we be designing post-work economic systems rather than desperately clinging to employment as the primary means of distributing resources?

The plumber advice might be missing the point. Instead of training for the last remaining jobs, maybe we should be training for the first post-work society.

If you can't answer either question clearly, maybe it's time to research plumbing programs. Or maybe it's time to start demanding a different conversation about what comes next.

The choice isn't between human work and AI replacement. It's between managed transition and chaotic collapse.

Adapt & Create,

Kamil

There's one thing that's often overlooked: humans always want things that are hard to get. When AI makes productivity abundant and all products and services become cheap, our needs and desires simply move on to other things that are hard to get. The attention of a stranger, a silent spot in the city, a roundtrip to the moon, two minutes with Oprah, watching every scifi movie ever created, a hamburger from moose meat, a hike passing through all European capital cities, a kiss from a porn star, a wedding at the bottom of the ocean, the honest empathy of a non-machone therapist. There's no end to the things that are hard to get, which means there's no end to human needs and desires. And where there's demand, there is supply. Where there's supply, there is labor.

Yes. I’d add that AI challenges not just work, but also identity.

And too often, our response is reactive: save the economy, retrain the workers, don’t fall behind. But what if this moment isn’t just a threat … it’s a test of values? What do we protect, what do we surrender, and who gets to decide?

The real danger isn’t AI … it’s not a good vs evil story … but to your point … what we do with this powerful technology … I’ve been writing a lot in this too. Happy that this framing is coming across other writers