From AI Panic to AI Culture in 2026

Your playbook for building internal AI confidence without the corporate chaos

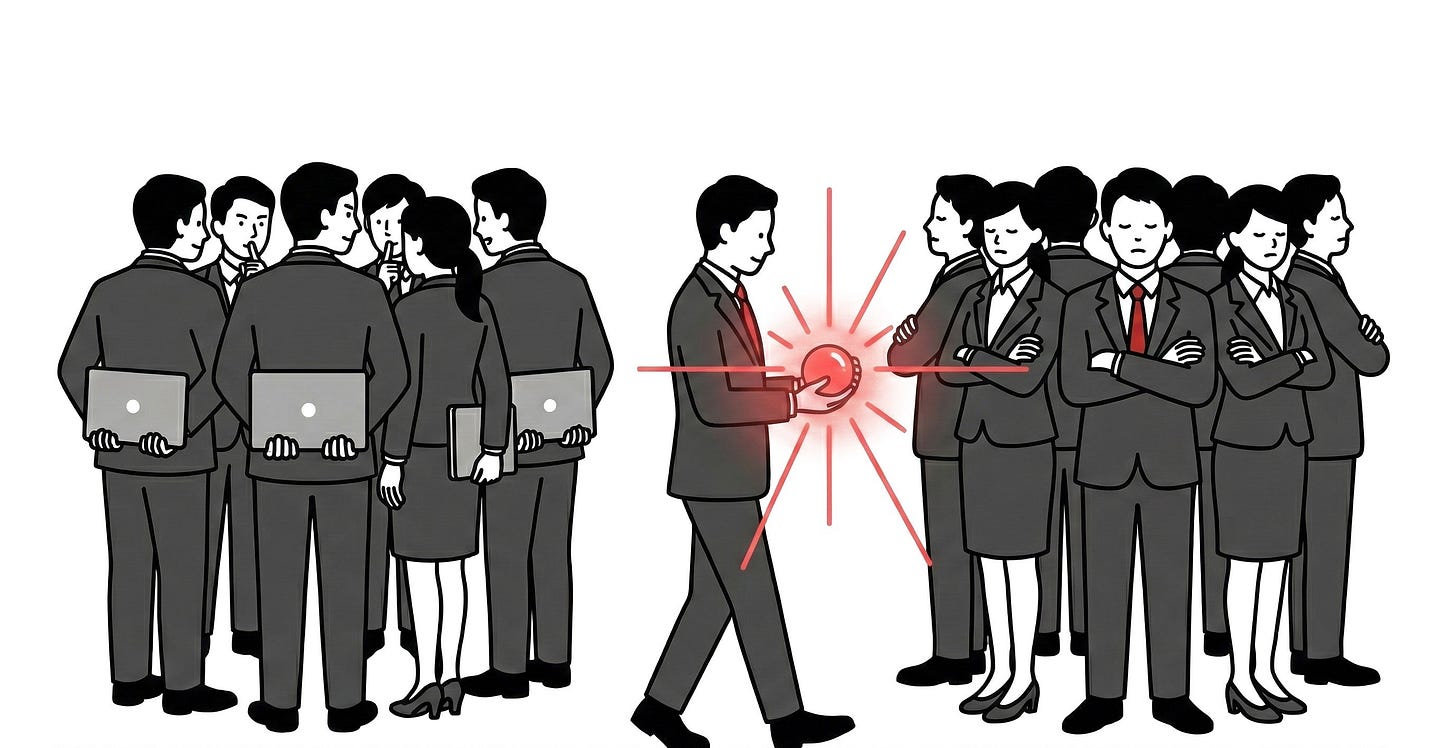

TLDR: Most companies have two AI camps: secret users and nervous avoiders. Both are failing. This year, the gap between AI-confident and AI-anxious teams has become visible in promotions, headcount, and results. Build a 3-5-person task force, run an amnesty audit of current usage, create one-page guidelines, and select pilot projects based on frustration, not features. The goal isn’t AI fluency. It’s AI confidence.

This week’s premium editions:

⭐️ Sidequest: Join the beta of my first vibe-coded startup rightclickprompt.com

Hey Adopter, happy Saturday!

Your company has an AI policy. You’ve never seen it written down. It goes like this: use it secretly, tell no one, and hope IT doesn’t notice.

Meanwhile, the person down the hall is avoiding AI entirely. They’re convinced they’ll break something, get flagged by compliance, or worse, look stupid. They’ve decided waiting is safer than trying.

Table of Contents:

Both strategies are losing. One creates data security nightmares hiding in plain sight. The other creates skill gaps that widen by the month.

“The most expensive AI strategy is the one nobody admits you have.”

This split is happening in almost every organisation right now. And it’s costing more than anyone’s measuring.

Why this year is different

You’ve heard “this is the year of AI” for three years running. Fair. The hype fatigue is real. But here’s what changed: the tools got boring.

That sounds like an insult. It’s a compliment. Boring means reliable. Boring means useful for actual work, not demo day. Boring means your finance team can use it without a computer science degree.

The gap between teams who figured this out and teams still “exploring options” is no longer theoretical. It’s showing up in who gets promoted, who gets budget, who lands the client.

“AI doesn’t replace people. AI-confident people replace AI-anxious people.”

This isn’t about becoming a technical wizard. It’s about becoming the person who knows how to get things done faster. And that advantage compounds.

The foundation layer

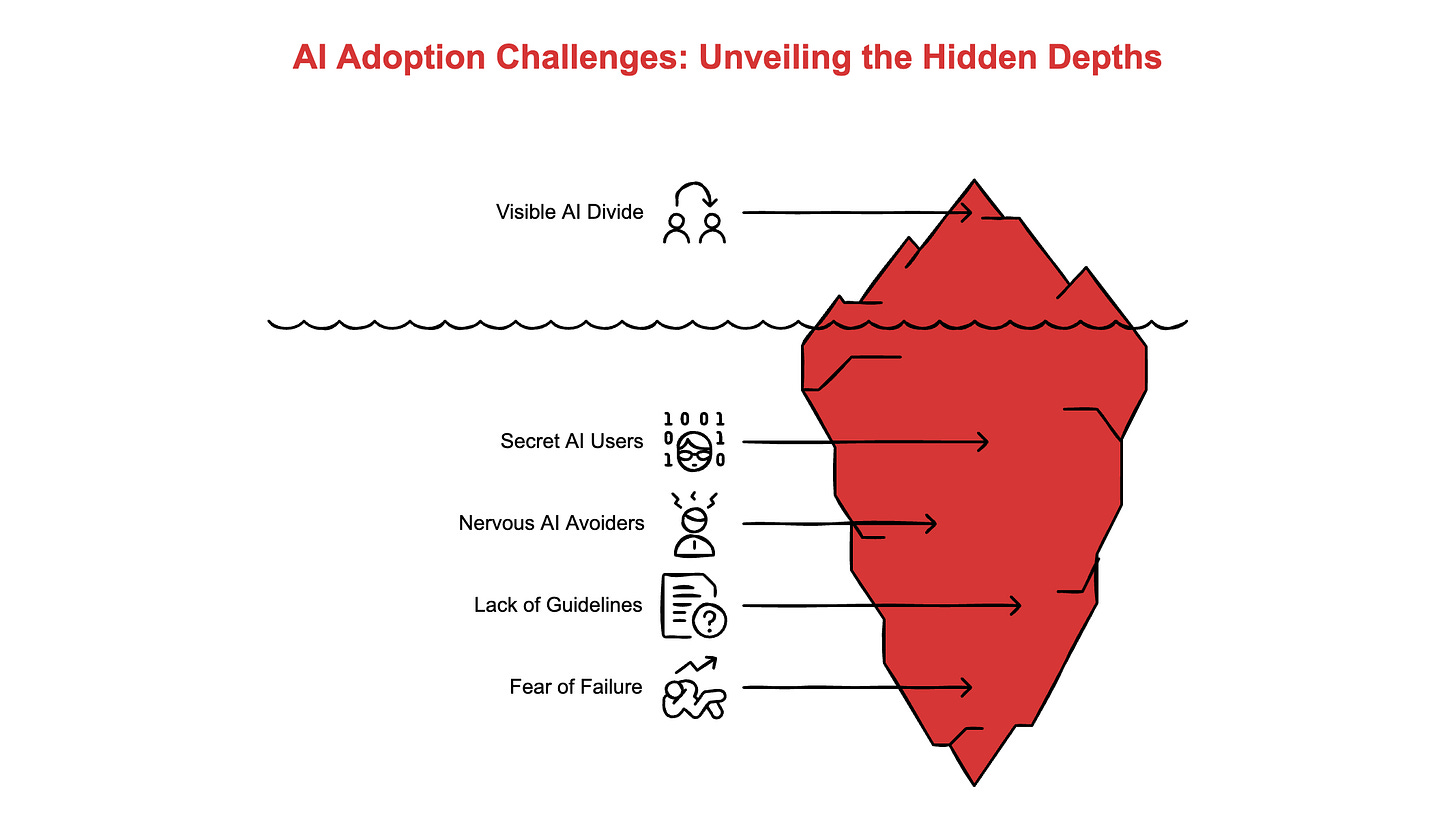

Your first instinct will be to form a committee. Resist it. Committees produce documents. You need 3-5 people who produce experiments.

Your task force needs:

The person who’s already been tinkering with Claude or ChatGPT on their lunch break. They exist. They’re hiding it.

The ops lead who hates manual data entry and has complained about it for two years.

Someone from legal or compliance who’s curious, not paralysed. They exist too, despite the stereotype.

An executive sponsor with enough authority to remove blockers and celebrate wins publicly. This doesn’t have to be the CEO, but it can’t be someone whose endorsement means nothing.

Give this group a simple charter: explore, test, report back. Thirty minutes a week. That’s the starting commitment.

Run an amnesty audit

Before you can move forward, you need to know where you are. And here’s the uncomfortable part: people on your team are already using AI. They’re not telling you because they’re not sure if they’re allowed.

Send a quick survey. Three questions:

What AI tools are you using right now?

What tasks are you using them for?

What’s working or frustrating?

Critical: Frame this as amnesty, not investigation. You’re not looking to punish. You’re looking to learn. If people feel like they’re confessing, they’ll lie. If they feel like they’re contributing, they’ll tell you everything.

You’ll discover two things: use cases you can formalise and security gaps you need to close.

Create one-page guidelines

You don’t need a 50-page policy. You need clear guardrails so people feel confident trying things.

Cover these basics and nothing more:

What not to upload: Client names, deal terms, financials, personally identifiable information. Unless you’re using an enterprise-grade tool with proper data handling, assume anything you type could leak.

What needs checking: AI outputs must be human fact-checked before external use. Period. No exceptions.

Who to ask: Name a real person. When someone’s uncertain about a use case, they need to know who can answer in 24 hours, not 24 days.

“You can’t automate chaos. Document before you delegate.”

That last line matters more than the guidelines themselves. Before any workflow becomes an AI pilot, it needs to be written down. Not because bureaucracy is good. Because you can’t teach AI to do something that three people do three different ways.

Where every department can start

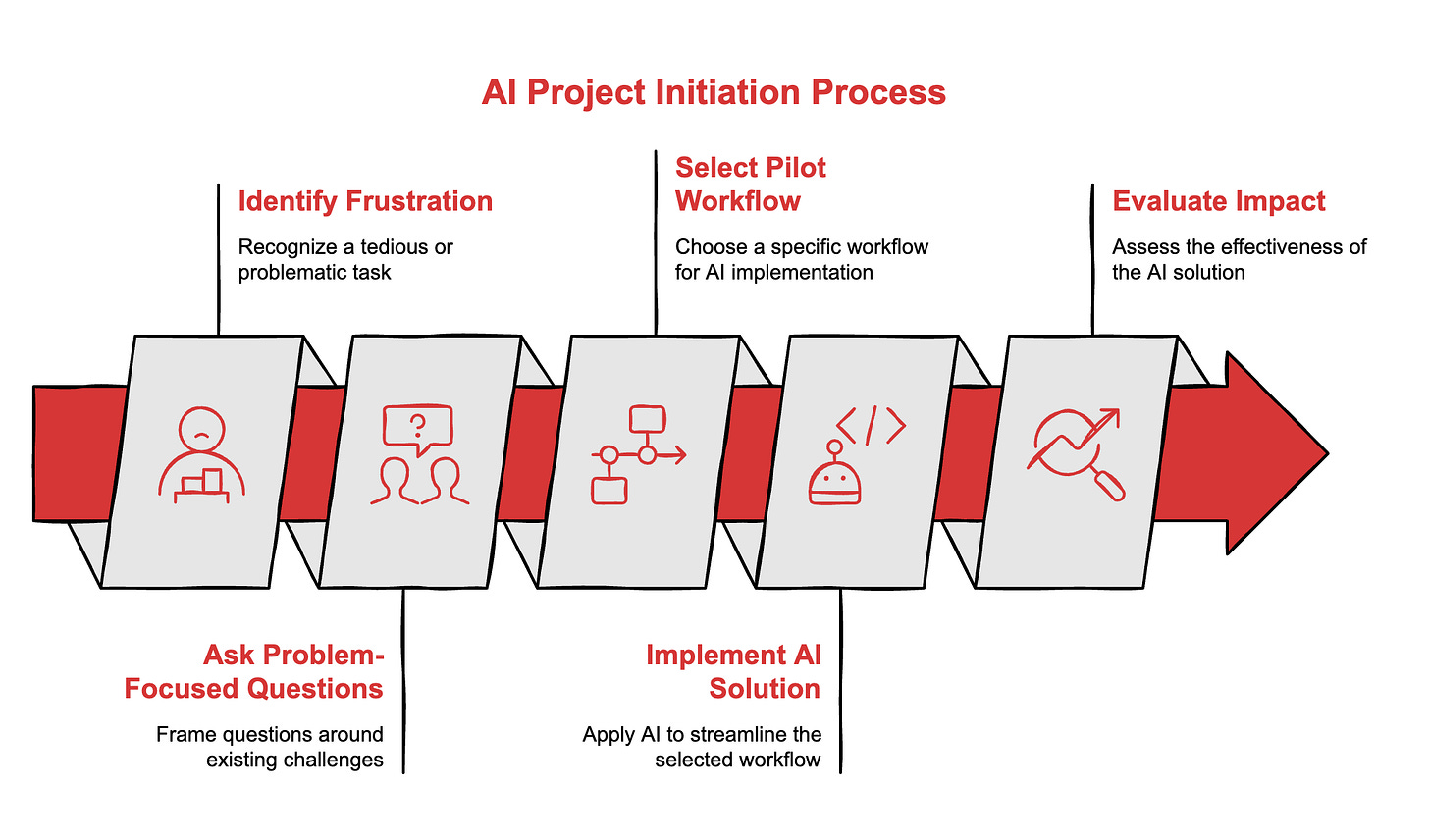

The best AI projects don’t start with technology. They start with frustration.

Don’t ask “How can we use ChatGPT?” Ask “What takes too long? What’s tedious? What do we keep getting wrong?”

“The best AI projects don’t start with technology. They start with the task nobody wants to do.”

Here’s where to look by department:

Finance: Expense coding, report generation, variance analysis, vendor communication templates. Finance teams don’t need AI to be smarter. They need it to stop copying numbers between spreadsheets.

HR: Job descriptions, policy Q&A, onboarding materials, interview question banks. HR isn’t looking for a robot recruiter. They’re looking for a first draft of the job description that doesn’t take 45 minutes.

Marketing: First drafts of content, social posts, research summaries, competitive analysis. The goal isn’t AI-generated content. The goal is AI-assisted speed on the parts that don’t require human creativity.

Sales: Proposal drafts, meeting prep, follow-up emails, CRM updates. Most salespeople spend more time on admin than selling. That’s backwards.

Operations: Process documentation, meeting recaps, vendor communications, project status updates. The ops lead who’s been begging for a better system? This is their moment.

Legal and compliance: Contract review prep, policy summarisation, regulatory research. The goal isn’t replacing legal judgment. The goal is getting to the judgment faster.

Pick one workflow per department. The one everyone hates. That’s your pilot.

The measurement trap

Most teams skip measurement because it feels like homework. Then they wonder why leadership won’t fund the next phase.

“If you can’t prove it worked, you’re not running a pilot. You’re playing with software.”

You don’t need precision. You need a baseline. Before you start, answer three questions:

How long does this task take right now? How many people touch it? How many revision cycles does it go through?

Ballpark is fine. If you think lease abstracts take somewhere between 2-4 hours, start with 3 hours as your baseline. Something beats nothing.

After three weeks, measure again. Time saved? Errors reduced? Fewer revision cycles? That’s your story for leadership.

One more thing: measure the qualitative too. Ask people how frustrating the old process was. Ask how confident they feel about the new one. Numbers convince executives. Feelings convince adoption.

Build feedback loops

AI adoption isn’t set it and forget it. Build in regular check-ins:

Weekly for the first month: 15-minute task force sync. What’s working? What’s breaking? What did we learn?

Monthly ongoing: Review metrics, adjust approach, share wins with the broader team.

Quarterly: Present results to leadership. Make the case for expansion. Or cut what isn’t working.

From panic to culture

The efficiency gains are nice. But they’re not the real win.

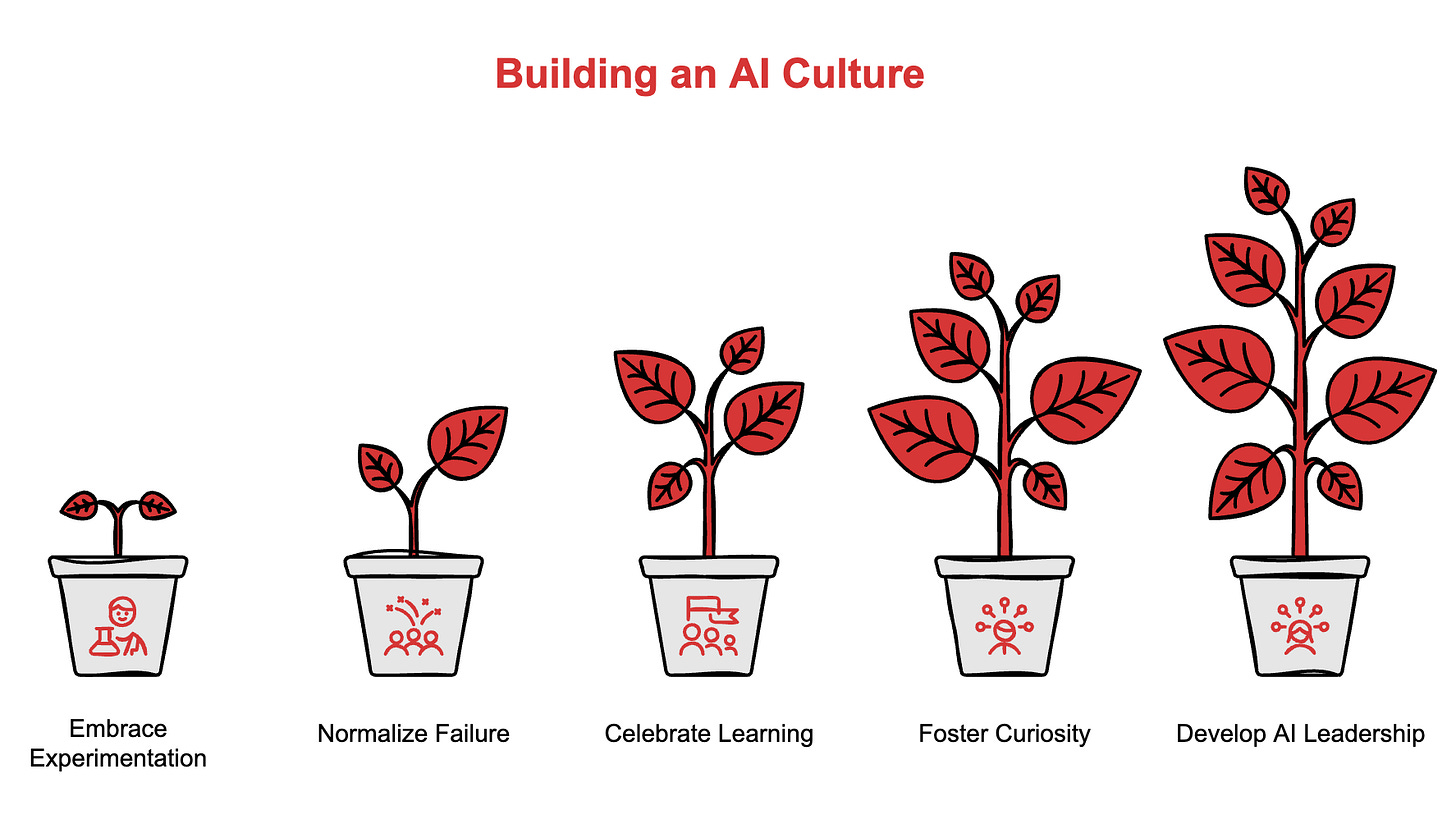

The real win is confidence. It’s the moment when trying something new stops feeling risky and starts feeling normal. When “I tested this and it didn’t work” becomes an acceptable sentence in a team meeting.

“AI culture isn’t about mastering tools. It’s about normalising the phrase ‘I tried something.’”

The organisations that figure this out won’t be the ones with the biggest AI budgets. They’ll be the ones where people feel safe to experiment, fail, learn, and try again.

Build that by celebrating experiments, not only successes. Run “show and tell” sessions where people share what they tried, even if it flopped. Make visible what used to be invisible: the curiosity, the tinkering, the willingness to look stupid for five minutes in exchange for learning something.

This is a leadership problem dressed up as a technology problem. And it’s one you can start solving this week.

The person who figures this out inside your organisation will be the one others turn to when leadership asks “What should we do about AI?” That person doesn’t need to be an engineer. They need to be curious, organised, and willing to try things in public.

Why not you?

Adapt & Create,

Kamil