The AI Leverage Ladder: Four Rungs That Decide Your next Career Move

Your job title doesn’t decide your AI-era career. Your position in the value chain does.

Hey Adopter,

Your career resilience now depends on one question: where do you sit in the AI value chain, and are you climbing?

The 95/5 split

Goldman Sachs CEO David Solomon told investors that AI now completes 95% of an IPO prospectus in minutes, work that once took a six-person team two weeks. His takeaway was blunt: the last 5% is where the value lives. Judgment, regulatory nuance, client understanding, strategic framing. Everything else is a commodity.

That 5% is not a quirk specific to investment banking. It’s a pattern showing up across every knowledge profession. PwC’s 2025 Global AI Jobs Barometer, analyzing one billion job postings across six continents, found that workers with AI skills command a 56% wage premium. Double last year’s number. The market is pricing something specific: closeness to AI’s inputs, not its outputs.

But “move upstream” is vague advice. You need a map. Which brings us to the ladder.

Take the AI Leverage Ladder assessment here → (2 minutes, no email required)

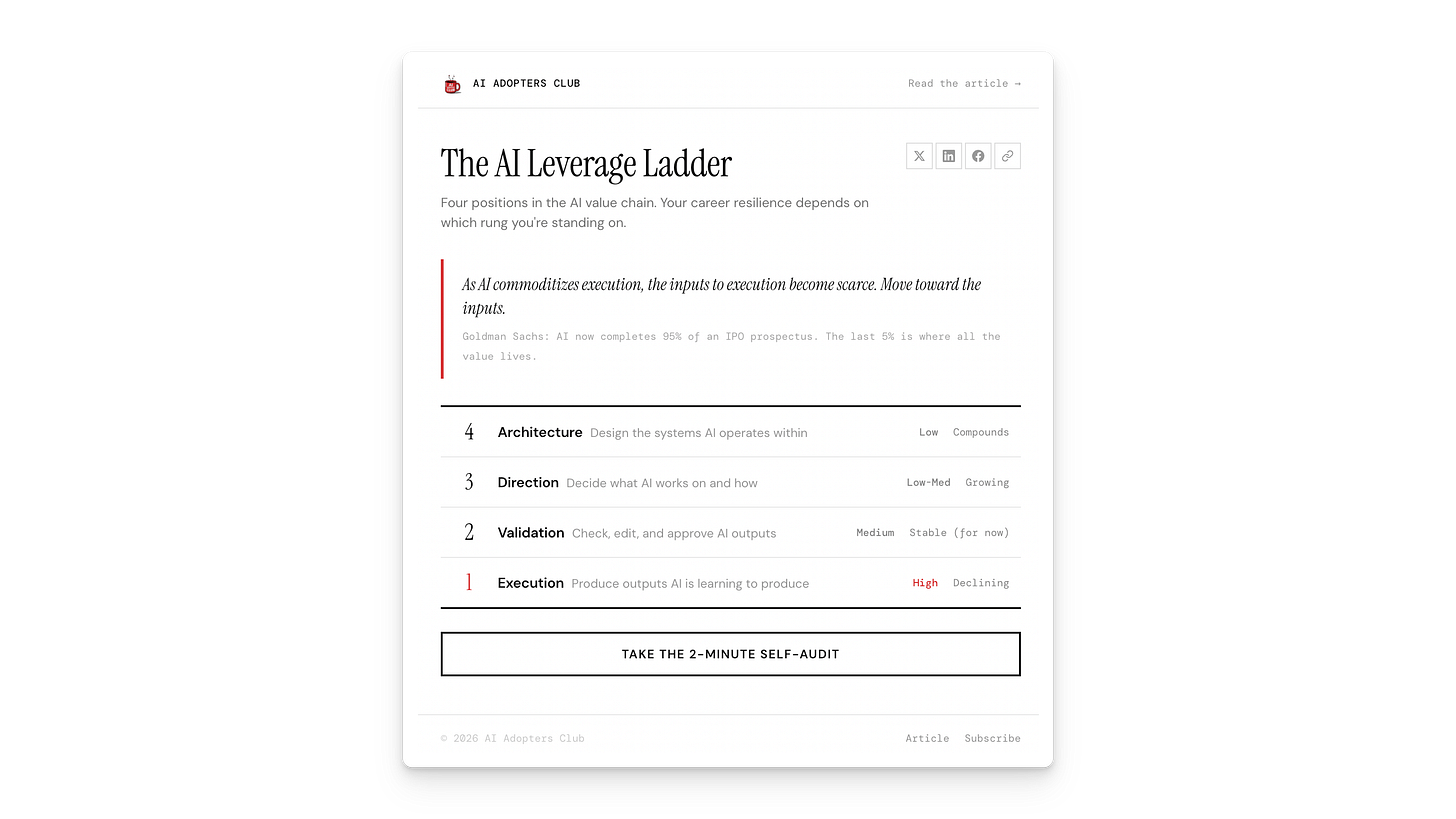

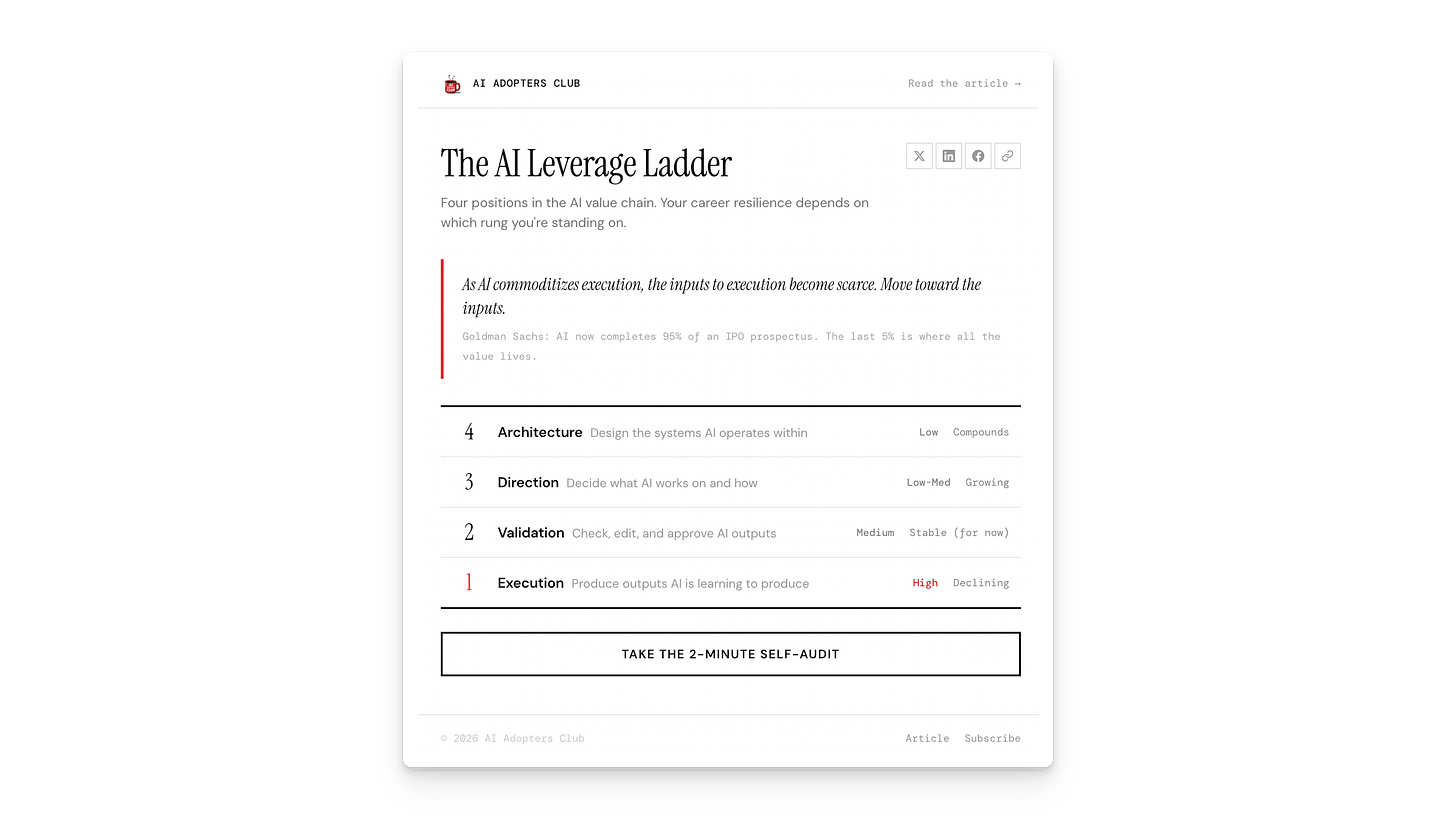

The AI leverage ladder

Think of your role as sitting on one of four rungs. Each rung represents a different relationship with AI, and each carries a different risk profile as these systems get better.

Rung 1: Execution

You produce outputs AI is learning to produce. First drafts, data entry, report generation, scheduling, basic analysis. This is where the compression hits hardest. Entry-level hiring dropped 73% at the P1 level between 2023 and 2025, and Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows US programmer employment fell 27.5% in the same period. If your day is mostly generating things AI generates faster, this is your rung.

Risk: High. Leverage: Declining.

Rung 2: Validation

You check, edit, and approve AI outputs. You’re the human in the loop. 76% of enterprises have built these roles specifically to catch hallucinations. Necessary work, and safer than execution for now. But reactive by nature. As models improve, the volume of errors drops, and so does the leverage of the person catching them.

Risk: Medium. Leverage: Stable, for now.

Rung 3: Direction

You decide what AI works on and how it should work. You scope problems, define success criteria, choose which tasks deserve AI and which don’t. UC Berkeley research found that the firms most successful with AI were those where people understood the problem deeply, not the technology. Domain expertise becomes the moat at this level.

Risk: Low. Leverage: Growing.

Rung 4: Architecture

You design the systems AI operates within. Data pipelines, governance standards, AI product strategy, ethical guardrails. Harvey AI, the legal tech company now valued at $8 billion, was co-founded by a first-year litigation associate who repositioned from drafting contracts to building the system that drafts contracts. At Moses Singer, 75% of lawyers now use Harvey, and younger associates shifted from first drafts to case strategy and argument testing. They climbed the ladder.

Risk: Low. Leverage: Compounds.

The pattern holds across industries. The question is where your own work sits. And that requires honesty about a trap most people don’t see coming.

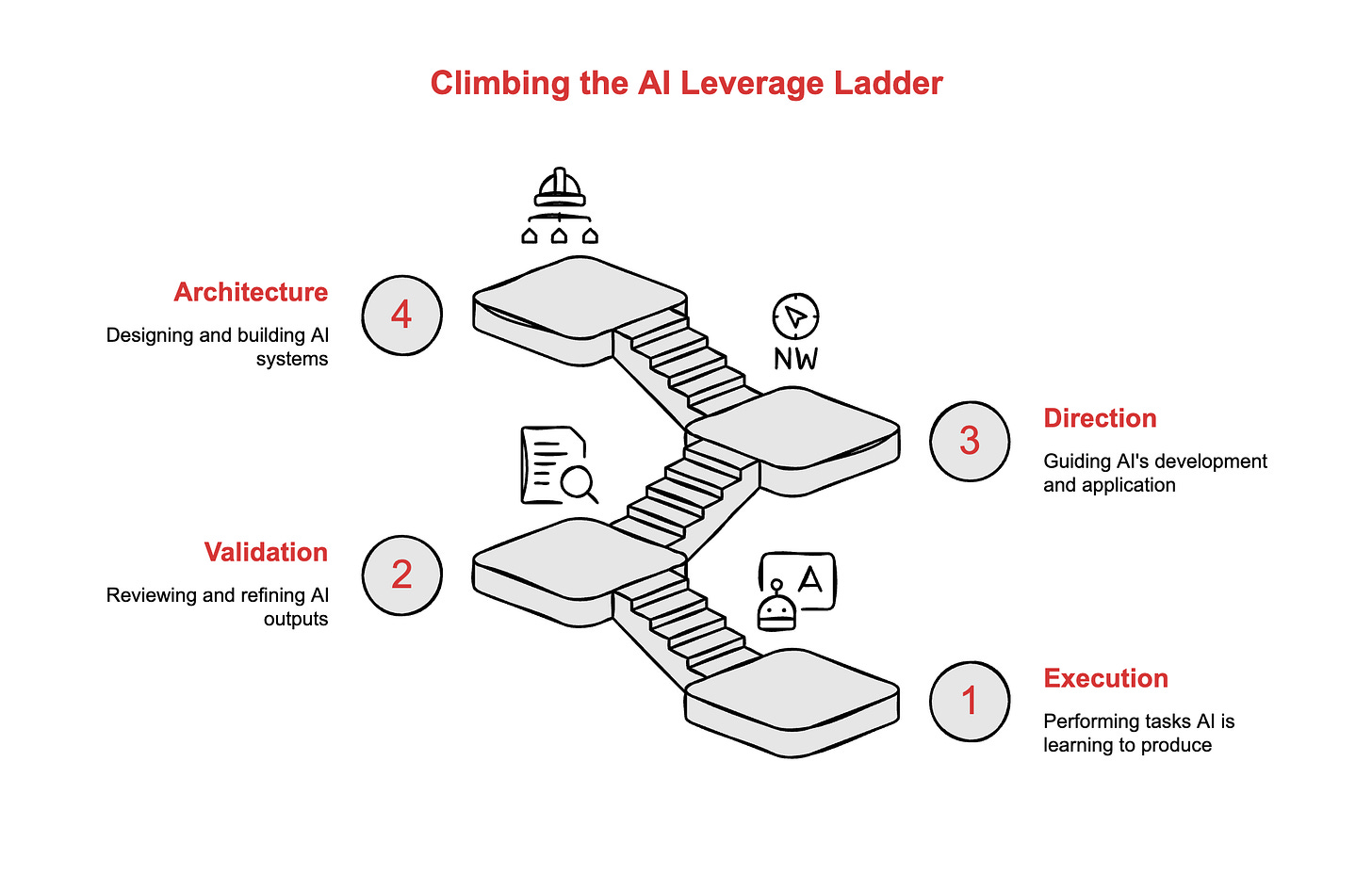

The cognitive debt problem

Here is where the ladder gets tricky. Climbing requires deep thinking, and AI usage is quietly eroding it.

MIT Media Lab researchers found that participants using ChatGPT showed a 47% drop in neural connectivity compared to unaided writers. 83% couldn’t recall key points from their own AI-assisted essays minutes after writing them. Worse, when they switched back to unaided work, their engagement stayed suppressed. The researchers called it “cognitive debt.”

Microsoft Research confirmed the pattern across 319 knowledge workers: higher confidence in AI leads to less critical thinking, which erodes self-confidence in your own skills, which drives even greater AI reliance. A loop that pulls you down the ladder while you think you’re climbing it.

The BCG/Harvard study of 758 consultants quantified the cost. For tasks outside AI’s capability range, consultants who trusted AI performed 19 percentage points worse than those working without it. AI made them faster on the wrong things and blind to the boundary between “AI handles this well” and “AI is confidently wrong here.”

Climbing the ladder means using AI to amplify your domain expertise, not replace the thinking that built it. Rung 3 and Rung 4 professionals stay valuable because they know where the model breaks, and that knowledge comes from deliberate, unassisted practice, not from delegation.

The Monday morning audit

Open your calendar and block 15 minutes. List your ten most frequent work tasks. Tag each one: Execution, Validation, Direction, or Architecture. Count the ratio.

Take the AI Leverage Ladder assessment here → (2 minutes, no email required)

If 60% or more of your work sits at Rung 1 or 2, your single highest-leverage move this quarter is to pick one Execution task and redesign it so you operate at the Direction level instead. Don’t automate your current job description. Redesign it one rung up.

The workers earning that 56% premium aren’t the ones who learned to prompt better. They’re the ones who repositioned closer to AI’s inputs, where judgment, domain knowledge, and strategic oversight create value that compounds with every model upgrade.

Goldman’s 95/5 split will only widen. The question is which side you’re building your career on.

Adapt & Create,

Kamil

This is exactly the type of conversations we should be having around AI- not the ones around AI doomsday reckoning. Thanks Kamil for providing an organized framework to visualise which level one fits in.

Love this ladder framing: way more actionable than the usual “learn to prompt” advice. I especially like the shift from job titles to “where you sit in the value chain”; it’s a clean mental model for deciding what to say yes/no to in your week.

The cognitive debt idea hit hard as well. Using AI to climb from Execution to Direction/Architecture only works if you protect some deep, unassisted thinking time, otherwise you’re just speeding up that very same commoditized work.