Scientists Spent $300 Million Simulating Brains; They Still Can’t Explain Yours

The strange gap between mapping 16,800 biochemical interactions and figuring out why you can’t focus after lunch

Hey Adopter,

This is a Sunday rabbit hole. No action items. No frameworks. Just a genuinely weird story about what happens when you throw 300 million Swiss francs at understanding the brain, and what it might tell us about the future of AI.

Grab a coffee. This one’s for thinking.

The most expensive ctrl+z in neuroscience

In December 2024, Swiss federal funding for the Blue Brain Project ended. Twenty years of work. 300 million Swiss francs. The kind of budget that makes your quarterly planning meetings feel quaint.

The project’s goal was absurdly ambitious: reverse-engineer the human brain inside a computer. Henry Markram, the neuroscientist leading the effort, wanted to build a complete digital simulation of how neurons fire, connect, and create... well, us.

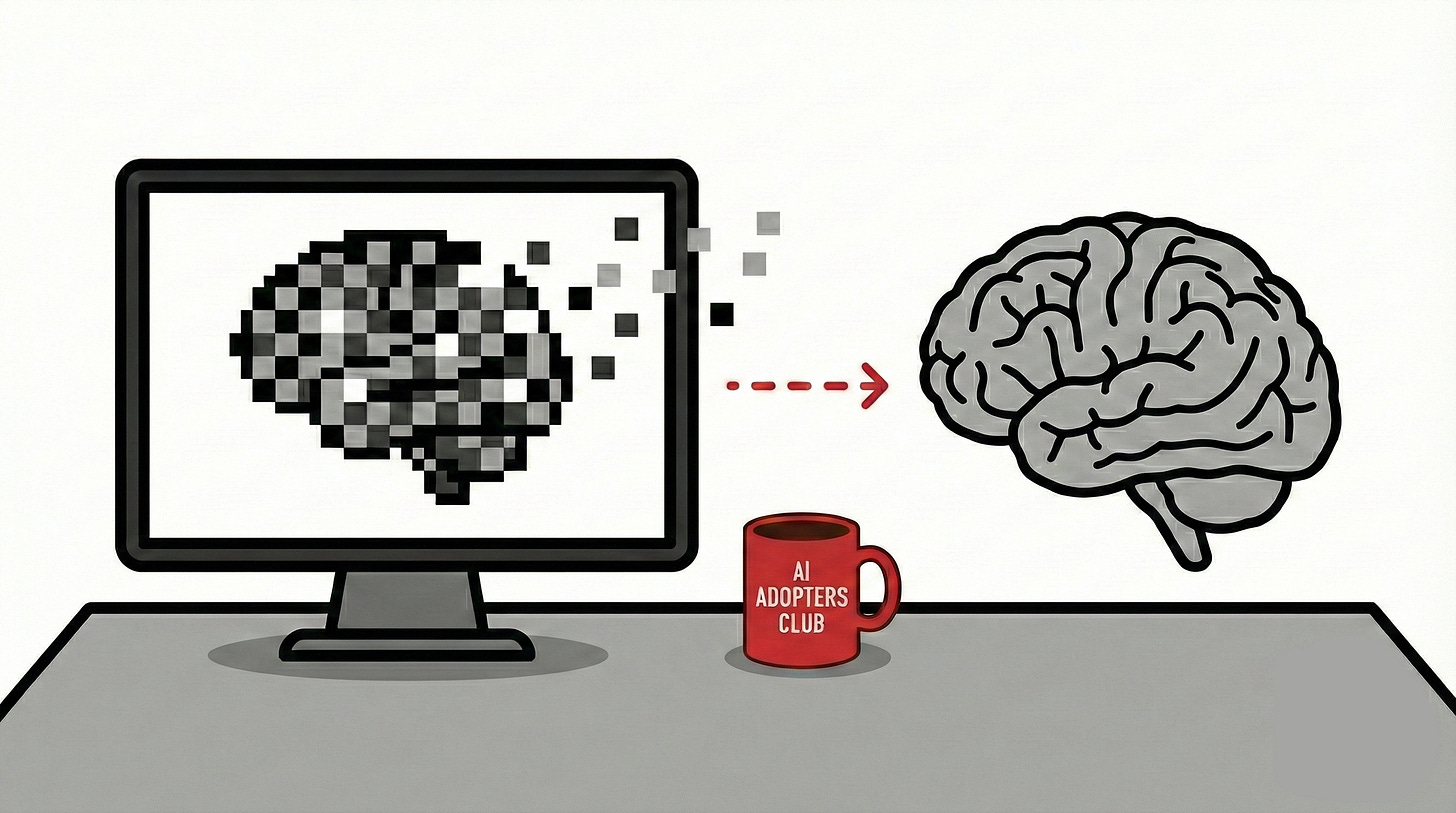

When the funding stopped, the team did something unexpected. Instead of shutting down, they open-sourced everything. On March 18, 2025, the Open Brain Institute launched as a non-profit foundation, releasing 18 million lines of code and petabytes of brain data to anyone who wants it.

That’s the equivalent of your company losing its biggest client and responding by publishing your entire playbook on GitHub.

The controversy nobody talks about at conferences

Markram isn’t a quiet academic. In a 2009 TED Talk, he claimed a functional artificial human brain could be built within ten years. That deadline came and went.

In 2013, he launched the Human Brain Project, a €1 billion European initiative. By 2014, over 800 neuroscientists had signed an open letter demanding an overhaul. The criticism was brutal. Markram was removed from leadership.

The core scientific objection is worth understanding. Peter Dayan of University College London called the assumption that we know enough to simulate the brain “crazy.” His argument: copying brain hardware tells you nothing about the software. You could replicate every neuron perfectly and still have no idea why your colleague Dave keeps replying-all to emails clearly marked “no reply needed.”

Filmmaker Noah Hutton spent a decade documenting the project for “In Silico.” He described finding fancy technological gadgets without clear outputs. Expensive machinery. Unclear meaning.

This is the baggage the Open Brain Institute carries into its next chapter.

What they actually built

Here’s where it gets interesting.

Despite the controversy, something tangible exists. The Open Brain Platform offers researchers AI-powered “Virtual Labs” where they can build digital brain models of any species, at any age, in any disease state. The platform opened to researchers on March 28, 2025.

In May 2025, OBI released what it called the most comprehensive computer model of brain metabolism ever built, mapping 16,800 biochemical interactions. The model demonstrated how diet and exercise could restore resilience to aged brain cells.

The organisation now operates with 43 former Blue Brain team members. Markram serves as President. His wife Kamila, CEO of scientific publisher Frontiers, serves as Vice President. They’ve also co-founded inait SA, an AI startup chasing artificial general intelligence through digital brain research.

Markram presented the work at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January 2025. His pitch: “The brain is the only known system that exhibits true generalised intelligence. OBI’s virtual labs can be used to study how the brain’s natural architecture creates intelligence, offering radical new directions for AI.”

Bold claim. The jury’s still out.

Why this matters for AI

The honest answer: we don’t know yet.

Every AI lab talks about “intelligence” without being able to define it. We’ve built systems that can write poetry, generate code, and beat humans at games we invented. We still can’t explain why you remember your childhood phone number but forget where you put your keys this morning.

OBI is betting that understanding biological intelligence, the only working example we have, will unlock something useful for artificial intelligence. Maybe they’re right. Maybe they’re chasing shadows. Either way, the foundation structure allows them to pursue partnerships across pharma, biotech, and AI sectors.

EPFL continues to support the transition. Sometimes institutional relationships outlast individual controversies.

Meanwhile, in the brain you already have…

Scientists are spending hundreds of millions trying to simulate neural activity. You’re running the real thing right now, and it comes with its own operating challenges.

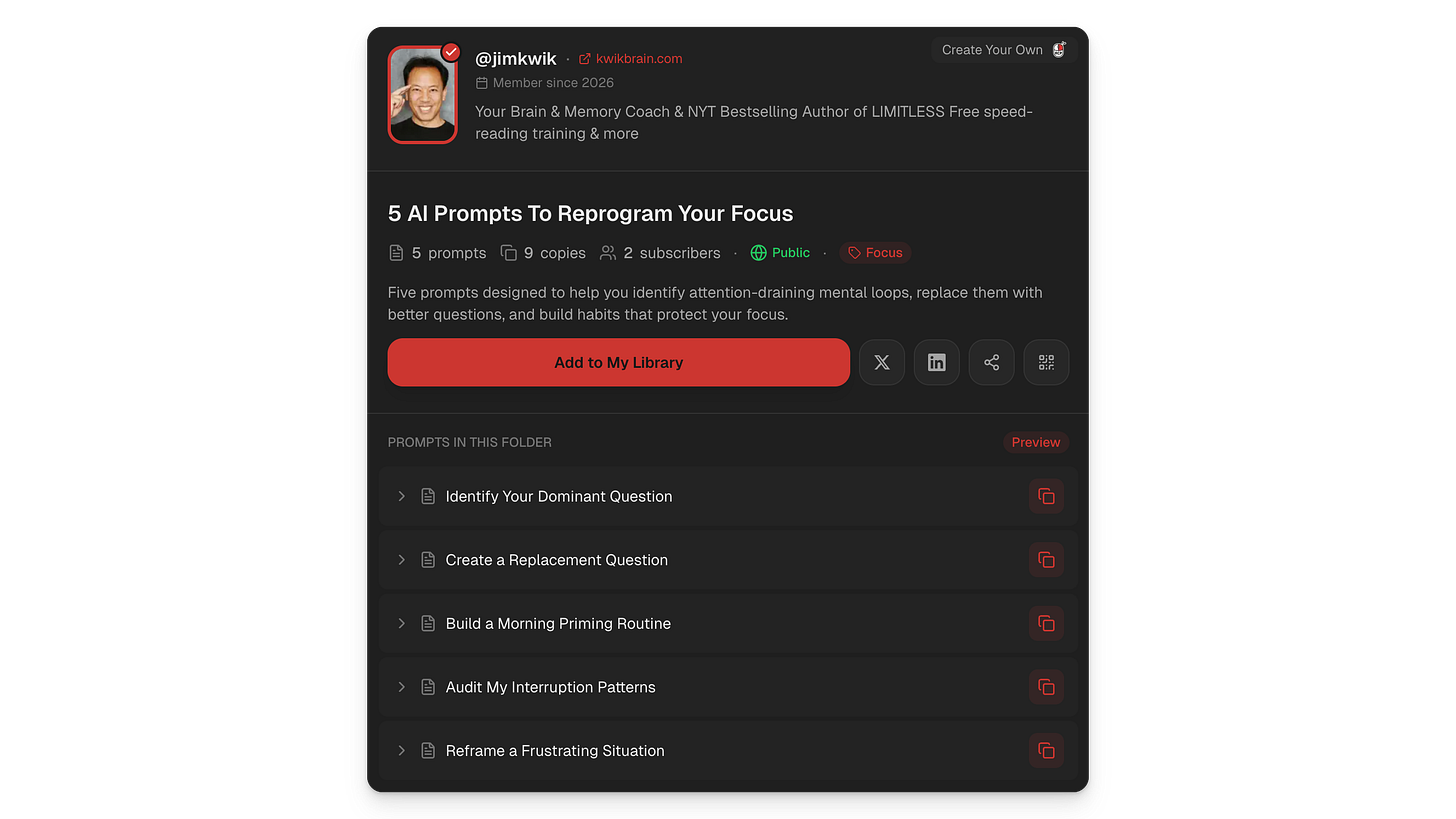

My friend Jim Kwik, one of the top brain and memory coaches working today, has been exploring how to actually use the brain you’ve got more effectively. He’s dropping a newsletter on this topic tomorrow that’s worth reading.

He also put together a prompt pack for AI Adopters Club readers. Five prompts designed to help you identify attention-draining mental loops, replace them with better questions, and build habits that protect your focus.

We can’t simulate 16,800 biochemical interactions yet. But we can ask better questions of the brains we already have.

Adapt & Create,

Kamil

Neuroscientists still can't completely model a worm with a few thousand neurons. There's far more going on chemically at each synapse than simple electric signals.