Tax Agencies Are Building AI That Sees Everything You Own

Nine governments built AI systems that recovered billions. Then auditors found 74% of the models lack ethics reviews.

Hey Adopter,

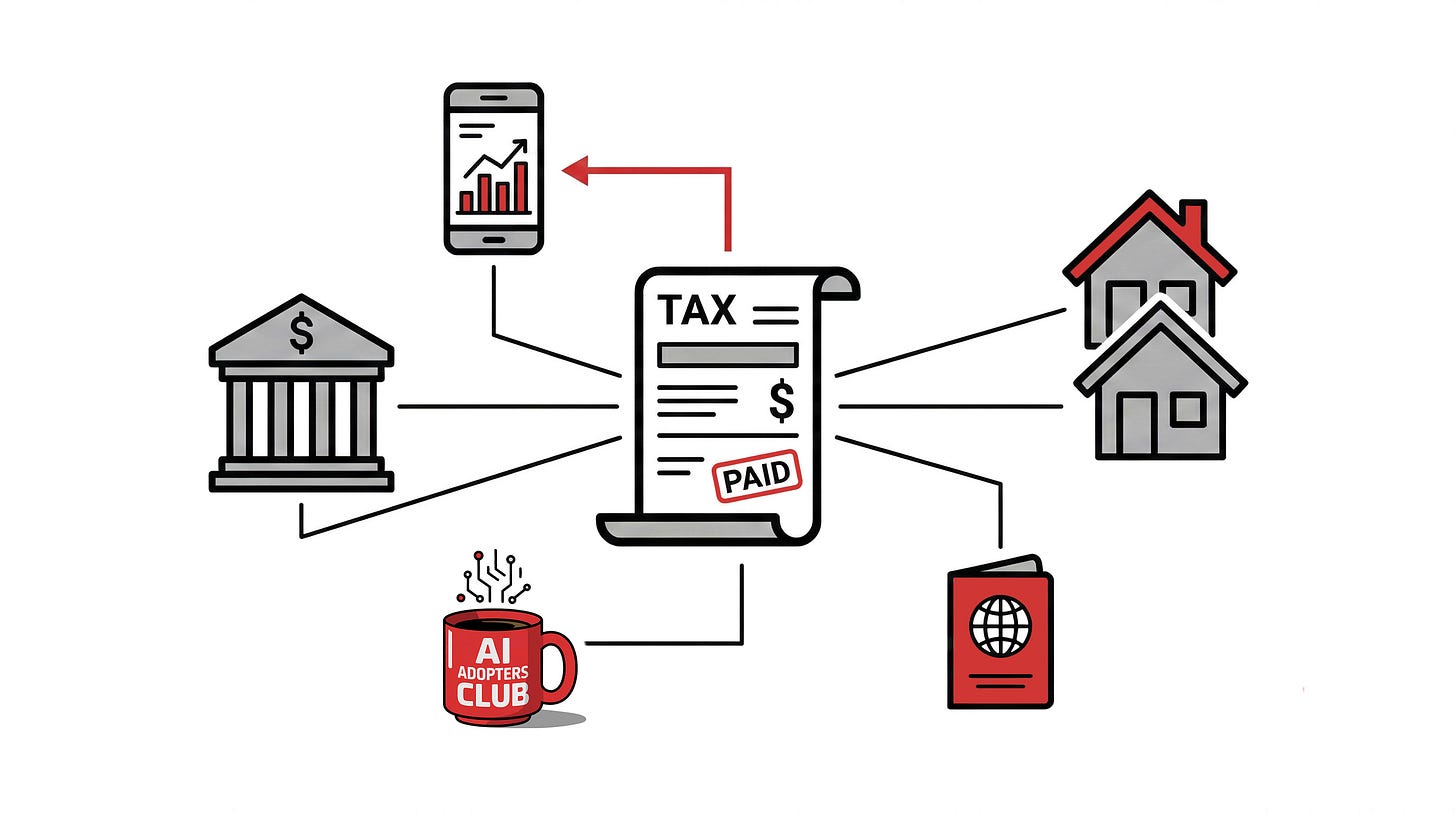

Tax authorities have quietly become the most aggressive AI adopters in government. The UK’s system recovered £4.6 billion last year. France uses satellite imagery to find undeclared swimming pools. India scrapes Instagram to match luxury purchases against declared income.

The technology works. The governance doesn’t. That tension is the story.

What “Tax Administration 3.0” actually means

The OECD coined the term to describe a shift most people haven’t noticed: the end of voluntary compliance.

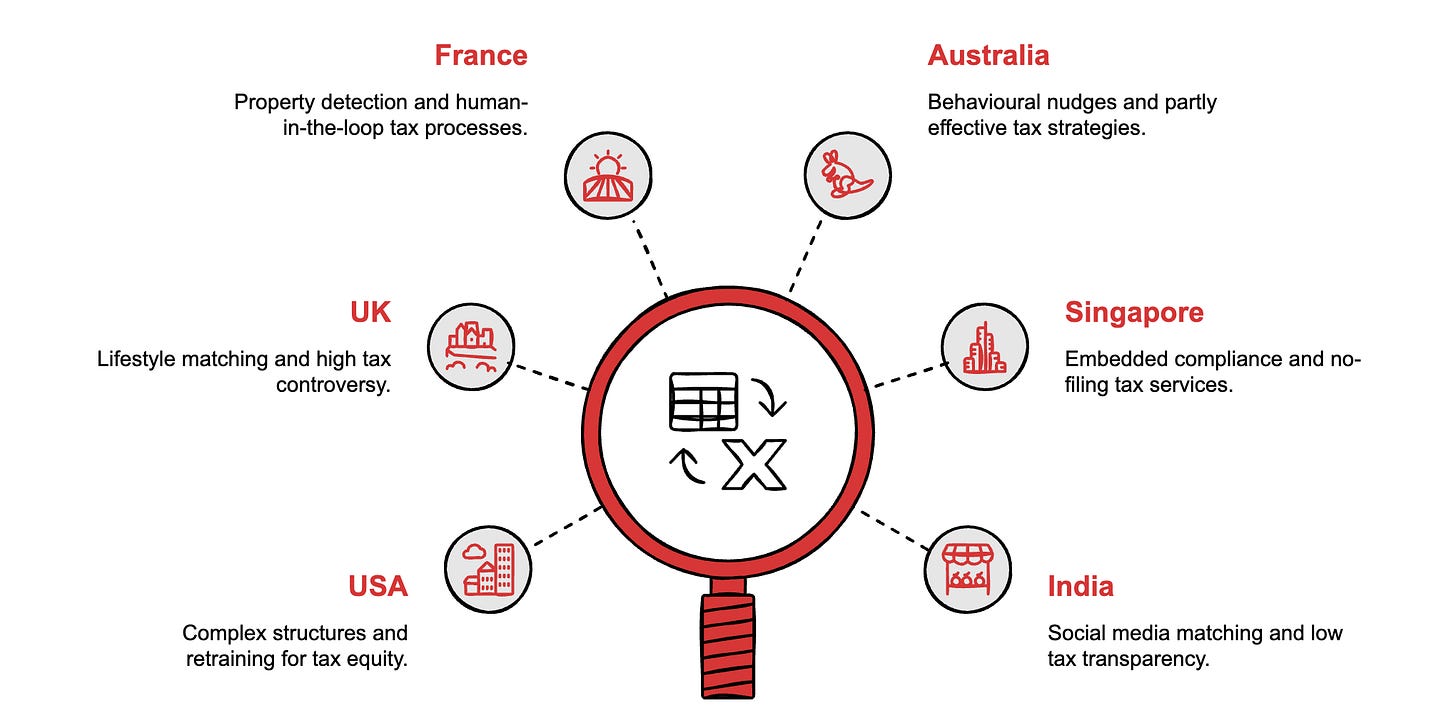

Traditional tax collection works like this: you file a return, the government checks some percentage of returns, mistakes and fraud slip through. The US tax gap exceeds $600 billion annually. That’s the difference between taxes owed and taxes collected.

The new model flips the sequence. Governments ingest data in real-time from banks, employers, property registries, and online marketplaces. AI cross-references these streams against your filing. Compliance gets “baked in” to the transaction before you even submit.

Singapore represents the endpoint. Their No-Filing Service pre-populates returns with 100% accuracy for many taxpayers. You log in, review what the algorithm calculated, and click accept. AI-selected audits recover three times the revenue of random selection.

Brazil goes further. Companies cannot issue a valid invoice without the tax authority’s servers signing it first. The state has real-time visibility into every B2B transaction in the country.

The trajectory is clear: the tax return is dying. Within a decade, most citizens will receive a bill or a refund generated by AI, with the option to accept or challenge.

That brings us to the problem.

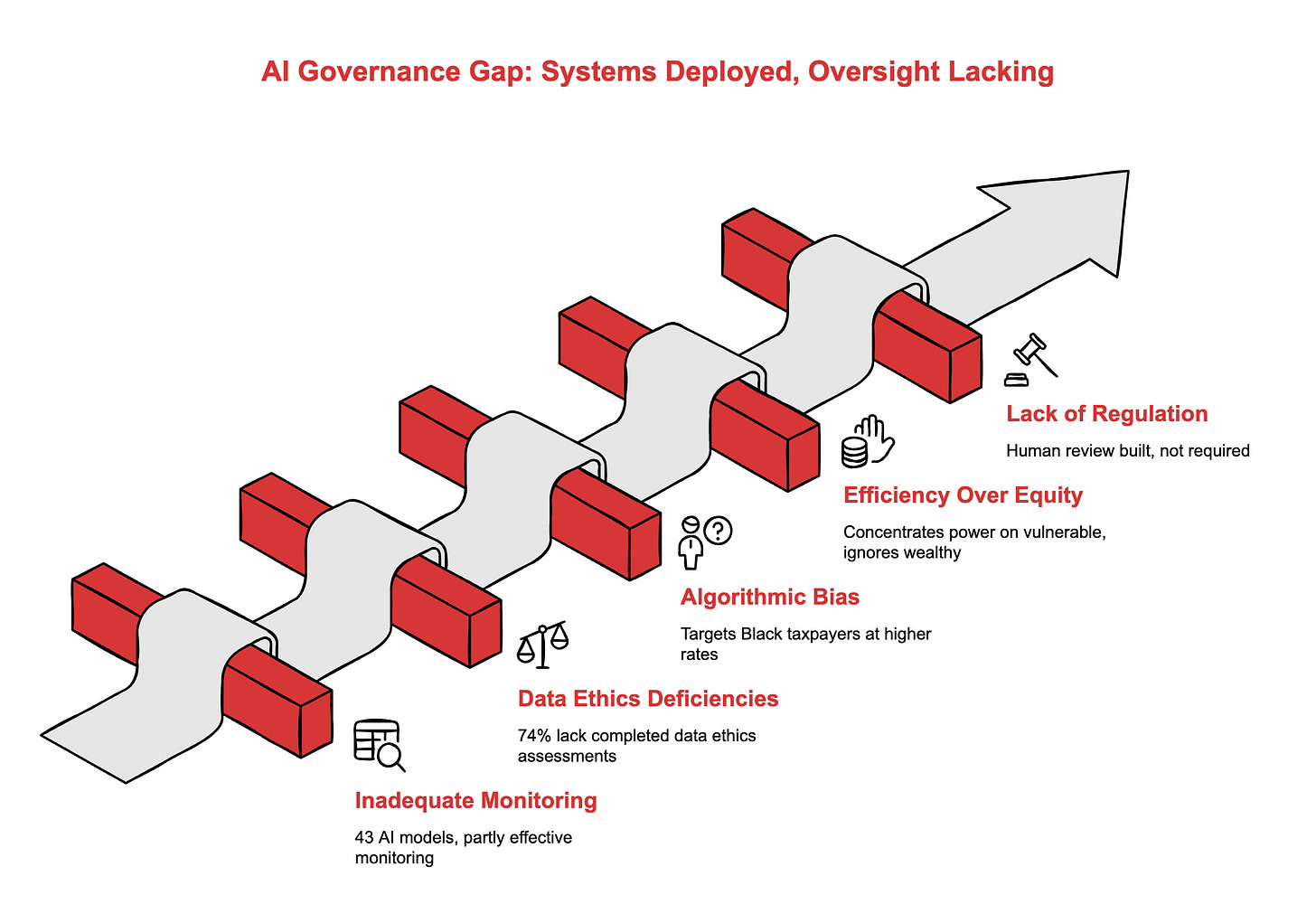

The governance gap

The systems are deployed. The oversight isn’t ready.

Australia: The National Audit Office examined the ATO’s AI deployment and delivered a damning verdict. The agency runs 43 AI models in production with “partly effective” monitoring arrangements. 74% of these models lack completed data ethics assessments. This in one of the world’s most functional democracies.

United States: In 2023, Stanford researchers working with the Treasury Department proved that IRS audit selection algorithms targeted Black taxpayers at 2.9 to 4.7 times the rate of others. The algorithm wasn’t explicitly racist. It was optimised for efficiency. Auditing low-income Earned Income Tax Credit claims is cheaper than auditing complex business returns. Black taxpayers are overrepresented in EITC claims due to systemic economic factors. The algorithm learned the pattern.

The system achieved its objective. It also concentrated state coercive power on the vulnerable while ignoring the wealthy.

France: The swimming pool detection system had a 30% error rate initially, confusing blue tarps and trampolines for pools. The DGFiP instituted mandatory human review of every AI detection before issuing a tax bill. That safeguard exists because they chose to build it, not because regulation required it.

The pattern across jurisdictions: capability first, governance later. Or never.

The Palantir question

Here’s where the analysis gets uncomfortable.

Palantir Technologies now powers tax enforcement infrastructure in both the United States and United Kingdom. The IRS awarded contracts to build a “unified data layer” using Palantir’s Foundry platform. HMRC uses Palantir to extend its Connect system’s capabilities.

The technology solves a real problem. The IRS runs 60+ different case management systems written in languages including Assembly code from the 1960s. Palantir’s ontology layer lets modern AI tools query this legacy data as if it were a modern database. It maps relationships between entities: “Person A is a partner in Entity B which owns Asset C.”

The controversy is equally real. Members of Parliament have questioned UK government Palantir contracts following a Swiss security report. Civil liberties groups raise concerns about using “war-fighting” software for domestic administration. The fear: data flowing to a US defence contractor creates sovereignty risks and potential intelligence exposure.

The UK government’s response has been to sign bigger contracts.

This creates an interesting dependency. Western tax enforcement is increasingly running on proprietary infrastructure owned by a single US defence technology company. Whether that concerns you depends on your priors about government, technology, and power.

What’s in the full report (premium section):

Technical deep-dive on how each of the nine systems actually works, from the UK’s 30-database Connect architecture to Brazil’s real-time invoice signing

The Stanford bias study findings in full, including the mechanism that made the algorithm “correct” and unjust simultaneously

Vendor ecosystem analysis: who builds these systems, what the contracts look like, and the sovereignty risks of Palantir concentration

Comparative maturity table across all nine jurisdictions with governance status

The trajectory through 2030: what “AI that does” means for tax enforcement and why the tax return is dying